Countdown to the 9th Asia Pacific Triennial: Iran & Laos

Zahra Imani working in her studio / Courtesy: Zahra Imani / View full image

The intensive research for every Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art provides many new opportunities to deepen our understanding of art from across the region. For the first time in the Triennial’s history, QAGOMA curators visited Iran and Laos to meet and talk with local artists and curators. In the third in a series of articles leading up to the Asia Pacific Triennial, Ellie Buttrose and Tarun Nagesh explore the context for contemporary art in these two very different countries.

Regional Snapshot

Iran

When APT first featured Iranian artists in its sixth iteration in 2009, the United Nations Security Council sanctions against this Islamic republic made it difficult to undertake curatorial research inside the country. Artists were selected with the help of curators from the region and through viewing artists’ work in international exhibitions outside Iran.

The UN sanctions were lifted in 2015, however, enabling curators from QAGOMA to travel to Iran for the first time late last year. Having researched from afar, and having worked directly with Iranian artists for many years (and with recommendations in hand from curators Tirdad Zolghadr and Azar Mahmoudian), we were finally able to meet and talk with artists, filmmakers, curators and writers to experience Tehran’s art scene for ourselves.[1]

Zahra Imani working in her studio / Courtesy: Zahra Imani / View full image

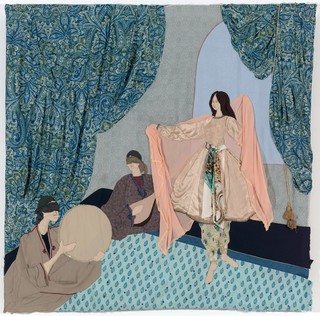

Zahra Imani, Iran b.1985 / Raqs no.2 2016 / Cotton/polyester, nylon, rayon, polyester, silk in appliqué technique / 250 x 250cm / Purchased 2018. QAGOMA Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Zahra Imani / View full image

In Iran, there is little support for contemporary art from the city or federal government, so it was a surprise to find that artist-run initiatives were not more prevalent. The majority of artists and dealers are based in Tehran, and the fast-paced art scene is dominated by commercial production, with limited infrastructure for critical reflection. The Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance closely monitors exhibitions. A focus on sales means that most art dealers change their exhibitions every two weeks, with only a few exhibiting the occasional more experimental project.

Emkan Art Gallery, which runs a strong project-based program, is the exception to this rule. But only a fraction of these shows are captured in short reviews that appear in a group thread on the mobile messaging app Telegram. After our first few days in Iran, we were left wondering what material art historians of the future will be able to access about the current Tehrani art scene.

A partial answer was found with curator Sohrab Kashani, who has been compiling catalogues, essays and posters in his library and making them publicly available through his independent initiative Sazmanab. Kashani is the Artistic Director of the recently established Pejman Foundation, where he is also building a library. Founded in 2015 by collector Hamidreza Pejman, the foundation held its first major exhibition in 2017. Programming is spread across three sites, making it a large-scale player in Tehran’s contemporary art scene. We are keen to return to see how its presence will affect the wider arts community in the coming years.

Operating on a more modest scale is the nonprofit space New Media Society. Established as Parkingallery in 1998, it has fostered engaged artistic discussions through screenings, talks and residencies, using Skype to connect with speakers outside Iran. While the energetic Delgosha Gallery is a mix of artist-run initiative and commercial gallery, the director and artist Shabahang Tayyari spoke to us about the importance of providing a space for younger and more experimental practices. Artist and curator Samira Hashemi — who, with Mona Aghababee, runs Va Space, a non-for-profit gallery and residency space in Isfahan — gave us some insight into the scene outside the country’s capital.

An earthenware goblet on display at the Museum of Ancient Iran / Photograph: J Da Silva © QAGOMA / View full image

The wealth of public museums are dedicated to the country’s rich history of visual arts, including the extraordinary Museum of the Islamic Era. In 2009, the expansive APT6 film program ‘The Cypress and the Crow: 50 Years of Iranian Animation’ included Boz Bazi (Boz Game) 2007 by Moin Samadi. This short animation references a 5000-year-old earthenware goblet that depicts a goat leaping to eat the leaves off a tree through a series of sequential painted scenes. The original goblet, on display at the Museum of Ancient Iran, is unusual in that the images of the goat standing, jumping in mid-air, and then biting the top of the tree provide a sense of time and movement, serving as an early example of proto-cinema.

Another highlight of the research trip was the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMOCA). As well as being an architectural destination, the museum houses an internationally renowned but rarely seen collection acquired by Farah Pahlavi, wife of the last Shah of Iran, prior to the 1979 Islamic Revolution. After a six-year hiatus, the Tehran International Sculpture Biennial was held at TMOCA during our visit; standout works included a history of the museum’s Donald Judd sculpture by Homayoun Askari Sirizi, and Barbad Golshiri’s installation of ephemeral grave markers.

Cutting glass at Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian’s studio / © Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian Estate / View full image

We ended our time in Tehran with a visit to artist Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, who was preparing for the opening of the Monir Museum at the University of Tehran in December last year. The nonagenarian artist has donated more than 50 artworks to the museum. We were delighted to see on the wall of Farmanfarmaian’s studio a picture of her APT6 commission Lightning for Neda 2009, now in the Gallery’s Collection, which the artist still considers one of her finest works. This research trip was hopefully the first of many visits to Iran that will build ongoing relationships with artists, enabling us to commission internationally significant pieces by leading Iranian artists for future iterations of APT.

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Iran b.1924 / Lightning for Neda 2009 / Mirror mosaic, reverse-glass painting, plaster on wood / Six panels: 300 x 200 x 25cm (each); 300 x 1200 x 25cm (overall) / The artist dedicates this work to the loving memory of her late husband Dr Abolbashar Farmanfarmaian. Purchased 2009. QAG Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Estate of Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian / Photograph: N Harth © QAGOMA / View full image

Ellie Buttrose is Associate Curator, International Contemporary Art, QAGOMA

Laos

Laos remains one of the less represented South-East Asian countries in international contemporary art contexts; however, the landlocked country is enriched with a diverse cultural output from a range of ethnicities and traditions, as well as a thriving textile industry. Alongside this is a small but highly motivated group of experimental artists creating work — sometimes deliberately kept from public view — that captures aspects of contemporary life in Laos and explores the country’s complex history. Traditional painting has remained popular and is still the primary practice taught in art colleges, although a group of young artists equipped with the tools of media and technology promises to disrupt this dominance.

Mekong banks, Vientiane / Photograph: T Nagesh © QAGOMA / View full image

While public arts infrastructure is in a rather dire state in Laos, and the National Museum was indefinitely closed at the time of visiting, several smaller organisations and locations enliven the capital city of Vientiane. The well-attended COPE Visitor Centre is an educational and resource centre that tells the history of the air strikes that have left the country scarred and the continued presence of unexploded ordinances, a subject explored by some of the country’s leading artists. The markets along the Mekong River in Vientiane have been a hub for locals to sell paintings in the past, but, in recent years, a spattering of small galleries and artist-run spaces have sprung up around the city, providing a platform for more experimental practices among a collection of textile galleries.

Buddhist sculpture in Luang Prabang / Photograph: T Nagesh © QAGOMA / View full image

Looms at Ock Pop Tok Living Crafts Centre, Luang Prabang / Photograph: T Nagesh © QAGOMA / View full image

The former royal capital of Luang Prabang is a small picturesque city perched on the river between the hills and dotted with historic Buddhist temples, many of which house collections of Buddhist sculpture among expansive murals. The city is a centre for textiles drawn from different ethnic groups from around the country, and textiles and crafts are abundant in the galleries that line the main streets. The lively night markets offer fine examples of embroidery from the Hmong community, who gradually settled in the city from the mountains further north. The advent of narrative textiles draws on the country’s history of migration and conflict, and skilled artists making experimental works are beginning to make their mark in broader contemporary art contexts.

APT9 will represent Laos-based artists for the first time in the triennial’s history. The works of three artists demonstrate the diverse practices and changing approach to art-making in a small but exciting context — one where forms of art are often evolving outside conventional galleries, capturing and conveying the contemporary reality of life in Laos.

Tarun Nagesh is Associate Curator, Asian Art, QAGOMA

Watch | Time-lapse of Qiu Zhijie creating Map of Technological Ethics 2018 especially conceived for GOMA’s expansive long gallery

The 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art

24 Nov 2018 – 28 Apr 2019

Queensland Art Gallery and the Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA)

Endnotes

- ^ Ellie Buttrose travelled with José Da Silva, former Curatorial Manager, Australian Cinémathèque, and now Director, UNSW Galleries, Sydney.