Moment in the sun: Painting in APT9

Kushana Bush, New Zealand b.1983 / In signs 2018 / Gouache, metallic paint and pencil on paper / 41 x 54cm / The Taylor Family Collection. Purchased 2018 with funds from Paul, Sue and Kate Taylor through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Kushana Bush / View full image

As QAGOMA’s flagship exhibition, the Asia Pacific Triennial is an internationally renowned event that is years in the planning and months in the making. Taking over both Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art and involving almost all staff, each APT features hundreds of works, including significant acquisitions, large-scale commissions and breathtaking installations. However, editor Rebecca Mutch also found some quiet moments to savour in APT9.

Qiu Zhijie’s soaring brush-and-ink map and Iman Raad’s eye-catching panelled mural are unmissable features. Zico Albaiquni’s paintings within paintings — with their iconic depictions of artists, artworks and taxidermied animals, their fluorescent pops of colour and irregularly shaped, multi-panel canvases — have also become firm favourites with visitors.

Qiu Zhijie

RELATED: Qiu Zhijie

Qiu Zhijie, China b.1969 / Map of Technological Ethics 2018 / Synthetic polymer paint / Site-specific wall painting, Gallery of Modern Art / Commissioned for APT9 / © Qiu Zhijie

Iman Raad

RELATED: Iman Raad

Iman Raad, Iran/United States b.1979 / Days of bliss and woe (installation view, detail) 2018 / Acrylic on plywood and wood / 119 panels: 122 x 121.5 x 0.5cm (each); 308 frames: 112.5 x 3.8 x 1.9cm (each) / Commissioned for APT9 / Purchased with funds from Tim Fairfax AC through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation 2018 / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Iman Raad / Photograph: Natasha Harth © QAGOMA / View full image

Iman Raad’s Garden nights (installation view, detail) 2018 / Courtesy: The artist / View full image

Zico Albaiquni

RELATED: Zico Albaiquni

Zico Albaiquni, Indonesia b.1987 / When it Shook – The Earth stood Still (After Pirous) 2018 / Oil and synthetic polymer paint on canvas / 120 x 200cm / Purchased 2018. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Zico Albaiquni / View full image

Installation view, GOMA / © Zico Albaiquni / Photograph: Natasha Harth © QAGOMA / View full image

Painting in APT9

After working on the catalogue for six months prior to the exhibition opening, I find it incredibly rewarding to see these works firsthand after experiencing them for so long through galley proofs. And while the works by Qiu, Raad and Albaiquni are truly astonishing, both in their subject matter and in their execution, I have also been seduced by a number of quieter moments — artworks that offer contemplative experiences for those willing to take a little more time walking through the gallery spaces.

Kushana Bush

Kushana Bush, Aotearoa New Zealand b.1983 / Death on a Pale Horse 2018 / Gouache, metallic paint and pencil on paper / 47 x 46cm / The Taylor Family Collection. Purchased 2018 with funds from Paul, Sue and Kate Taylor through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Kushana Bush / View full image

New Zealand artist Kushana Bush draws inspiration from many different cultures and periods of art history: Mughal and Persian miniature painting, European medieval manuscripts, Japanese ukiyo-e prints and European masters. Her intricately detailed gouache paintings explore universal themes — love and hate, revenge and salvation, devotion and rejection, good and evil — and illuminate the entanglements and riddles of human behaviour. Intimate in scale, her works are, however, dramatic in content.

Acts of devotion, scenes of torture, erotic couplings and strange scenarios abound. We try to make meaning in Bush’s complex paintings by connecting seemingly unrelated motifs, signs and symbols that are inspired by our shared lives, yet the resulting narratives seem unsettling and intense, with some bordering on the traumatic. Bush’s is a world of fantasy and intrigue rendered in delicate tones with a precise and knowing eye. We are seduced by its colour palette, decorations and patterns, and fascinated by the puzzle of intertwined bodies. Ultimately, we are witness to thoroughly unnerving worlds, and we find ourselves asking: what is that figure doing to that other figure, to themselves, to that animal; what is being done to them?

Nona Garcia

Nona Garcia, The Philippines b.1978 / Untitled Pine Tree 2018 / Oil on wood veneer / 50 panels: from 30 x 35cm to 122 x 244cm (each, approx.) / Courtesy: The artist / Photograph: Natasha Harth © QAGOMA / View full image

With Untitled Pine Tree 2018 by Nona Garcia, we witness the ‘second life’ of a decades-old tree from mountainous Baguio City — ‘City of Pines’ — in the Philippines. Installed in GOMA’s Long Gallery, multiple oil paintings on wood veneer panels depict the branches of a felled Baguio City pine, drawing attention to the contrast between the organic and the manufactured.

The 50 paintings of branches and cones are installed to echo the reach of the tree’s crown, with the panels spanning some 18 metres. In its succession of new environments — first as specimens closely observed in the artist’s studio and then as paintings viewed in the gallery space — the tree is ‘resurrected’ after its destruction and dismemberment. As in Australia, demonstrations in Baguio City protesting the destruction of nature to make way for development may not always result in conservation action; however, Garcia’s careful and meticulous paintings in APT9 allow viewers to reflect on the grandeur of this particular tree, which once stood tall in the street where the artist lives, as well as all the others that are lost every day around the world.

Idas Losin

Idas Losin, Taiwan b.1976 / Floating 2017 / Oil on canvas / 135 x 179cm / Purchased 2019. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Idas Losin / View full image

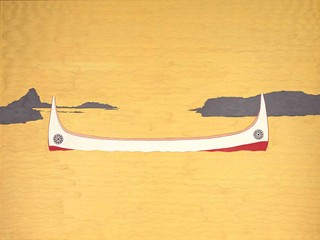

Sparse and dreamlike, the paintings of Taiwanese aboriginal artist Idas Losin are evocative renderings of islands and seascapes, in particular the islands of Lanyu (Orchid Island) and Jimagaod (Lesser Orchid Island), off the south-east coast of Taiwan. Her oil on canvas works depict the tatara fishing canoes of the Tao people — the tatara at rest, preparing to launch, and afloat in calm waters.

Decorated with both carved and painted emblems of the sea, ancestral beings and flying fish, the tatara, with their distinct upturned bow and stern and eyes at both ends, act as extensions of the human body and provide links between heaven and life on earth. Reflecting the significance of fishing for the Tao people, Losin’s sublime paintings — particularly Floating 2017, with its alternating brushstrokes of golden waves — embody moments of respite and stillness.

Pannaphan Yodmanee

RELATED: Pannaphan Yodmanee

Beautifully capturing the interconnectedness of art, religion and history in contemporary Thai society, and masquerading as the detritus and rubble of an abandoned and demolished building, is In the aftermath 2018 by Pannaphan Yodmanee. On closer inspection, the work reveals a wealth of Buddhist icons, crumbling stupas and small, delicate paintings executed in vivid temperas, gold pigments and mineral paints. With her installation, the artist invites us into a world of decaying murals in Thai Buddhist temples — murals that are in a constant state of deterioration and restoration.

The industrial materials of Yodmanee’s densely layered installation contrast with the traditional and precise painting techniques she learnt as a child at her local temple. Rocks and stones from the artist’s hometown represent the natural world, while found objects and fragments of buildings highlight the seemingly neverending cycle of urban destruction and renewal. Yodmanee draws her subject matter from disparate sources to chronicle South- East Asian histories of migration and conflict. In an affecting nod to its commission for APT9, the work also includes a subtle frieze-like rendering of Indigenous Australians, together with iconic birds and animals.

Pannaphan Yodmanee, Thailand b.1988 / In the aftermath 2018 / Found objects, artist-made icons, plaster, resin, concrete, steel, pigment / Site-specific installation, Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) / Commissioned for ‘The 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT9) / © Pannaphan Yodmanee

Just like the ‘major moment’ artworks from APT9 that are shared, tagged and liked on thousands of social media feeds, these deeply rewarding works by Kushana Bush, Nona Garcia, Idas Losin and Pannaphan Yodmanee also deserve their moment in the sun.

Rebecca Mutch is Editor, Information and Publishing Services, and editor of the APT9 exhibition catalogue.

The author thanks QAGOMA APT9 curators Reuben Keehan, Tarun Nagesh, Ruth McDougall and Abigail Bernal for sharing their words and insights about these artworks.

Watch APT9 videos or Read about artists / Know Brisbane through the QAGOMA Collection / Delve into our Queensland Stories / Read more about Australian Art / Subscribe to QAGOMA YouTube to go behind-the-scenes

APT9 has been assisted by our Founding Supporter Queensland Government and Principal Partner the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body, and the Visual Arts and Craft Strategy, an initiative of the Australian, State and Territory Governments.

Kushana Bush has been supported by Creative New Zealand.

Featured image detail: Kushana Bush, New Zealand b.1983 / In signs 2018 / Gouache, metallic paint and pencil on paper / 41 x 54cm / The Taylor Family Collection. Purchased 2018 with funds from Paul, Sue and Kate Taylor through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Kushana Bush

#APT9 #QAGOMA