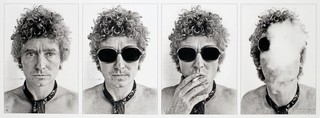

William Yang: portraits

William Yang, Australia b.1943 / Brett Whiteley (detail) 1975, printed 2021 / Inkjet print on Ilford smooth cotton rag art paper / 74 x 155cm / Purchased 2023 with funds from an anonymous donor through the QAGOMA Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © William Yang / View full image

Queensland-born, Sydney-based artist William Yang describes a moment in Sydney when a number of creative groups came together to generate an artistic wave that swept across Australian society.

My Generation

The intersections of the tight literary circle of Nobel award winner Patrick White (illustrated) and his partner, Manoly Lascaris, with the theatrical circle, their friends Jim Sharman and actress Kate Fitzpatrick. Fitzpatrick, in turn, models frocks in the exuberant fashion parades organised by designers Linda Jackson and Jenny Kee, while artists Peter Tully and David McDiarmid extend the tongue-in-cheek Australiana of the two fashionistas’ outfits with witty accessories. Their parades and parties at retail outlet Flamingo Park, a magnet for influential people in business, politics and the arts, determined the look of the 1970s and early 1980s. Tully and McDiarmid used their bravura visuals to jump start the Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, giving the event its unique and unforgettable style. The pair lived out a parallel lifestyle that might epitomise the Australian story of gay liberation, with its heady rush unfolding into aching tragedy.

Patrick White #1, living room, Martin Road 1988

William Yang, Australia b.1943 / Patrick White #1, living room, Martin Road 1988 / Gelatin silver photograph on paper / 45.6 x 36.4cm (comp.) / Purchased 1998. QAG Foundation Grant / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © William Yang / View full image

Golden couple Brett (illustrated) and Wendy Whiteley enjoyed the creative atmosphere of the swinging ’60s and the plunge into a riotous world of sex, drugs and rock’n’roll. Yang shows Brett painting, smoking and partying with the beautiful people, and his eventual deterioration as heroin took a fearful hold. The early death of their beautiful daughter, Arkie, was another aspect of this fated family history. Linda Jackson and Jenny Kee eventually split; Kee takes Danton Hughes, the son of Robert Hughes, as a lover; Danton suicides; Kee takes up Buddhism. Yang portrays lives that unfold, flower or wither: lives lived.

Brett Whiteley 1975

William Yang, Australia b.1943 / Brett Whiteley (detail) 1975, printed 2021 / Inkjet print on Ilford smooth cotton rag art paper / 74 x 155cm / Purchased 2023 with funds from an anonymous donor through the QAGOMA Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © William Yang / View full image

William Yang, Australia b.1943 / Brett Whiteley 1975, printed 2021 / Inkjet print on Ilford smooth cotton rag art paper / 74 x 155cm / Purchased 2023 with funds from an anonymous donor through the QAGOMA Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © William Yang / View full image

William Yang performing in front of an image from 1976 of Cressida Campbell, Jenny Kee and Stephen MacLean as part of his My Generation performance at the national Portrait Gallery, Canberra, December 2008 / Courtesy: William Yang / View full image

Yang’s generation is not life as reported in the newspapers but ‘as I saw it’: a personal account summed up as a litany of parties, of innocence lost and worldliness gained, a continuum of his search for contact and meaning. Like his contemporaries Rennie Ellis or Michael Rosen, William Yang is a social photographer, a recorder of life. His strength lies in creating a living testament, and his medium’s strength is that it is necessarily shared. He offers no moral tale, nor any notion of karma to underscore the events: just the three basic but vital stories — birth, love and death.

Life Lines

A major commission by William Yang was a feature in ‘The China Project’. ‘William Yang: Life Lines’ was installed at the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) 14 March to 28 June 2009.

Yang produced two new projects: Life lines, a large collage of portraits of family members, interspersed with pictures of historical Chinese sites in Australia, reflecting the diversity of the local Chinese community, and a series of self-portraits that trace Yang’s life from early childhood to the present.

‘William Yang: Life Lines’ installed in ‘The China Project’, Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) 28 March – 28 June 2009 / View full image

‘William Yang: Life Lines’ installed in ‘The China Project’, Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) 28 March – 28 June 2009 / View full image

Lifelines 2009

William Yang, Australia b.1943 / Lifelines 2009 / Inkjet print / 86 x 184cm / Courtesy: William Yang / View full image

Alter ego 2001

William Yang, Australia b.1943 / Alter ego 2001 / Digital inkjet print on rag paper / 68 x 88cm / Courtesy: William Yang / View full image