Tony Albert gives familiar objects a new voice

Installation view ‘Tony Albert: Visible’, 2 June – 7 October 2018 / Photograph: N Harth © QAGOMA / View full image

Tony Albert has obsessively collected what he calls ‘Aboriginalia’ since his childhood. His artistic practice involves collaborating, repurposing and reimagining popular culture paraphernalia, social and political movements, in order to tell the stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

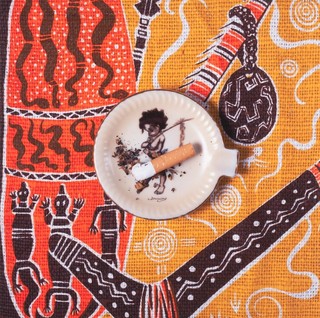

Recognisable to an Australian society of the not-so-distant past, and drawn from the trinket cabinets of many white Australian households of the 1950s and 60s, the kitsch ashtrays and decorative boomerangs that feature in Albert’s works also float in our collective subconscious, like fragments in a vast psychological universe, discarded, until now: Albert, an empathetic, opportunistic thrift-store shopper, rescues them. Unearthed and re-contextualised, he renders them strange and reveals the uneasiness behind their existence.

Since childhood, Tony Albert has been a collector of Aboriginalia.

Watch | Tony Albert introduces you to his Aboriginalia

Contemplation (from 'Mid Century Modern' series) 2016

Tony Albert, Girramay/Yidinyji/Kuku Yalanji peoples, Australia b.1981 / Contemplation (from 'Mid Century Modern' series) 2016, printed 2018 / Pigment print on Fine Art Hahnemühle Smooth Cotton (Photo Rag) 308gsm paper / 100 x 100cm / Purchased 2018. QAGOMA Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Tony Albert / View full image

Vintage pinball

Vintage pinball machine from the Tony Albert collection of Aboriginalia. / View full image

Installation view featuring Headhunter 2007

An installation view featuring Tony Albert’s Headhunter 2007 / Purchased with funds provided by the Aboriginal Collection Benefactors’ Group 2007 / Collection: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney / © Tony Albert / View full image

Interesting fact

One of Albert’s earliest collections, and his most substantial, is of vintage Aboriginalia – objects produced for commercial consumption (in tourist, design or art markets) featuring ‘Aboriginal’ images. Growing up in regional Queensland and suburban Brisbane, Albert accompanied his family on regular trips to local thrift shops, and among the piles of second-hand clothing and discarded household ephemera, Albert would often find objects decorated with Aboriginal-like designs or faces. Something about these pseudo-Aboriginal objects appealed to the Aboriginal boy living in white Australian suburbia.

By themselves, these items are simply fragments of an ignorant past; en masse, however, Albert sees them as the remnants of a much larger historical meteor, with the power to change the landscape of our own personal planets. The objects commonly depict naked children playing with animals; bearded men — naked or with a loincloth — often wearing a headband and holding a tool of some description (usually a boomerang or spear); or young women with bared breasts. The figures are set within a landscape — the ubiquitous xanthorrhoea or eucalypt nearby — or dancing around a fire. Sometimes their bodies are painted, or there are patterns painted on their tools. Perhaps it was a way for white Australia to connect indirectly with Aboriginal culture without having to interact with any individuals; hence, the proliferation of tea towels, plates, paintings on black velvet backgrounds, ashtrays, coasters, playing cards and small sculptures — cultural collateral that captured only the vaguest likeness of Aboriginal peoples. Albert uses these same objects to tell the stories of the people they replaced. He gives them back their dignity, while bringing to light the contemporary issues that stem from our unresolved history. Through his practice, Albert says what we already know in a way that we can process, using objects familiar to us — using humour to depict the brutal truth. Sometimes, the poison is also the antidote.

Brothers (details) 2013

Tony Albert b.1981, Girramay/Yidinji/Kuku/Yalanji peoples / Brothers (details) 2013 / Courtesy: Tony Albert / View full image

Tony Albert / Girramay/Yidinji/Kuku/Yalanji peoples / Brothers (details) 2013 / Collection: The artist / View full image

Albert’s works, which are culturally and historically educational, and created with an optimistic stance, make our unsettling past seem almost palatable — at least, at first. The history is uncomfortable; he merely asks us to remember it, and to guard against its repetition, offering a way forward so that the cycle can be broken. Artists such as Destiny Deacon, Daniel Boyd, Brook Andrew and Vernon Ah Kee also repurpose and reclaim objects and imagery of Aboriginal people. More often than not, the images these artists rework were originally taken by ethnographers or anthropologists, and without the permission of those depicted. These artists highlight the stereotypes and misrepresentation of an entire country of sovereign First Nations peoples, and bring them back into our living, breathing society. The works remind the viewer that living descendants of these same misrepresented subjects are able to tell their own stories, and tell them truthfully.

The artist, Carriageworks Studio, 2018 / Photograph: Mark Pokorny / View full image

In Albert’s 2010 reworking of Daddy’s Little Girl 2 1994 by Gordon Bennett (one of his greatest artistic influences), he addresses Bennett directly, saying that: ‘The cycle of racism is ever present. We must hope that it will be broken’.[1] The production of culturally problematic mass media, the derogatory items in tourist shops, and the social stereotyping of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, can’t be changed overnight, but, in the name of breaking the cycle, Albert takes items that are typically belittling — be they media stories, objects or historical events — and shows the individualism behind them. He reframes his chosen subject in a way that is true to his lived experience and the experiences of those around him. By reclaiming the dispossessed and misrepresented in history, and instilling the truths, or perceived truths, he hopes that there will be real change in our world.

Warakurna The Force is with us #2 2017

Tony Albert, David C Collins and Joel Spring / Warakurna The Force is with us #2 2017 / Courtesy: Tony Albert / View full image

Tony Albert has spent a lot of time supporting other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in their careers. He inspires and encourages curators, artists, art workers, community members and elders to tell their stories, and he works in many different corners of the art world — as a mentor, board member, collaborator, judge, panellist, collector, donor. In 2003, Albert and a group of artists established the proppaNOW collective, to challenge an art market that expected them to produce ‘dot’ paintings, and to create a network of conceptually like-minded artists. proppaNOW provided mentorships and encouragement — a mode of practice that he continues in his solo career, by facilitating workshops and collaborations all over the country. For Warakurna – The force is with us 2017, he worked with 40 artists from the Warakurna community; Pay attention 2009–10 involved 25 artists, including Richard Bell, Vernon Ah Kee, Archie Moore, Judy Watson, Judith Inkamala and others; and he worked on Frontier wars (Flying Fox Story Place) 2014 with Alair Pambegan, just to name a few. It seems fitting that Albert’s first major solo exhibition, ‘Visible’, curated by Bruce Johnson McLean, is being staged in Queensland — it’s the home of his ancestors, it’s where he was born, and it is where his career as an artist was first realised and continues to be fostered.

In our globalised world, it is increasingly easy to connect with others and share our stories, while referencing the many social, political and historical happenings that influence our lives and culture. Albert taps into the use of social media, popular culture and familiar objects, such as refuse from fast food giant McDonald’s, the Star Wars movie franchise, and superheroes Spider-Man, Superman and the Hulk, to connect with, give power to and inject love and appreciation into people who feel forgotten by the rest of Australia. By using the familiar, and encouraging Aboriginal people to insert themselves into the picture, Albert gives many people and communities the tools to write themselves into the Australia we live in today.

Tony Albert is successful as an artist in part because he listens to history, and to the community. He believes we are ready, as a nation, to rewrite history and, this time, to include the stories of First Peoples (alongside the many races and religions we have shared this country with for over 230 years). This is not the reality of a distant future in a faraway time and place, but something that is already happening: we are collaborating, colliding, and our personal planets are undergoing their ‘big bang’ transformations. Albert is helping us to communicate across time and space.

Warakurna Superheroes #6 2017

Tony Albert, Girramay/Yidinji/Kuku/Yalanji peoples b.1981 / Warakurna Superheroes #6 2017 / Courtesy: Tony Albert / View full image

Coby Edgar is a Larakia, Jingili, Filipino and English woman from the Northern Territory. She is the Assistant Curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Tony Albert: Visible

2 June – 7 October 2018

Queensland Art Gallery (QAG)

Brisbane, Australia

Endnotes

- ^ The artist, quoted in Daddy’s Little Girl (after Gordon Bennett) 2010 (Watercolour and pencil on paper, printed ink on paper, painted timber blocks / Dimensions variable / Private collection, Israel), as noted in Hetti Perkins and Maura Riley, Tony Albert, Dot Publishing (an imprint of Art & Australia Pty Ltd), Paddington, New South Wales, 2015, pp.50–1.