eX de Medici: Hollywood, the patriarchy & political power

eX de Medici’s The System 2023 (dressmaker: Michael Marendy) is based on her three-panel watercolour System (This is the Place Where the Martyrs Grow) 2023 (illustrated). It is the second garment the artist has collaborated on, the first being Shotgun Wedding Dress/Cleave 2015 (dressmaker: Gloria Grady Design (illustrated).

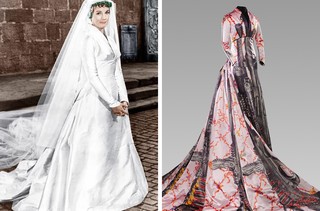

Julie Andrews in the wedding gown from ‘The Sound of Music’ (1965) | eX de Medici ‘Shotgun Wedding Dress/Cleave’ 2015

Installation view ‘eX de Medici: Beautiful Wickedness’, Gallery of Modern Art, 2023 / (Watercolour) eX de Medici, Australia b.1959 / System (This is the Place Where the Martyrs Grow) 2022 / Watercolour and tempera with gold leaf on paper / Three panels; two panels: 114 x 115cm; one panel: 114 x 145cm; 114 x 375cm (overall) / Collection: eX de Medici / © eX de Medici / (Dress) eX de Medici (Artist); Yianni Liangis (Collaborator); Gloria Grady Design (Dressmaker); RLDI (Rob Little Digital Images) (Photographer and digitisation); Think Positive Prints (Printer) / Shotgun Wedding Dress/Cleave 2015 / Digitally printed silk / 240 x 48 x 237cm / Purchased 2015 / Collection: National Gallery of Australia, Canberra / © eX de Medici / View full image

Both dresses were inspired by ‘costumes for Hollywood’ — the latter, the wedding gown that Julie Andrews wore as Maria in the perennially popular screen musical The Sound of Music (1965); the former, a figure-hugging silk crepe shift (illustrated) that Marilyn Monroe wore in her last, unfinished film, Something’s Got to Give! (1962), just prior to her untimely death.

Marilyn Monroe in ‘Something’s Got to Give!’ (1962)

Silk crepe shift Marilyn Monroe wore in her last, unfinished film, Something’s Got to Give! (1962) / Courtesy: Julien’s Auctions https://www.julienslive.com/lot-details/index/catalog/157/lot/66432 / View full image

Something’s Got to Give! (1962) Trailer

The System expands on de Medici’s dissection of toxic masculinity and patriarchal power structures, including the Hollywood system that has exploited a succession of talented and vulnerable women, and, in Monroe’s case, contributed to her demise. The gun that dominates the front of the dress points upwards, its barrel targeting an assumed female subject. The hands that are depicted crossed and metaphorically tied beneath the cowl on the back of the dress imply captivity and coercive control.

Samantha Littley, Curator, Australian Art, QAGOMA, and curator of ‘eX de Medici: Beautiful Wickedness’ taking a tour of the exhibition at the Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2023, wearing The System 2023 / Artist: eX de Medici; Collaborator: Samantha Littley; Dressmaker: Michael Marendy; Photographer and digitisation: RLDI (Rob Little Digital Images); Printer: Think Positive Prints / © eX de Medici / Photograph: Joe Ruckli © QAGOMA / View full image

The iconography in The System also explores political power, something that is more apparent in the related watercolour System (This is the Place Where the Martyrs Grow). Both artworks feature the Bushmaster AR-15 semi-automatic assault rifle that United States (US) forces used to fire on unarmed civilians from an aerial gunship in Baghdad in 2007, wrongly assuming they were insurgents. Iraqi Reuters journalists Namir Noor-Eldeen and Saeed Chmagh and nine others were killed in the attack, while two children were seriously injured. WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange later released footage of the atrocity online, intensifying attempts by the US to extradite him on charges of espionage.

eX de Medici ‘System (This is the Place Where the Martyrs Grow)‘ (details) 2022

eX de Medici, Australia b.1959 / System (This is the Place Where the Martyrs Grow) (detail) 2022 / Watercolour and tempera with gold leaf on paper / Three panels; two panels: 114 x 115cm; one panel: 114 x 145cm; 114 x 375cm (overall) / Collection: eX de Medici / © eX de Medici / View full image

eX de Medici, Australia b.1959 / System (This is the Place Where the Martyrs Grow) (detail) 2022 / Watercolour and tempera with gold leaf on paper / Three panels; two panels: 114 x 115cm; one panel: 114 x 145cm; 114 x 375cm (overall) / Collection: eX de Medici / © eX de Medici / Photograph: Rob Little Digital Images / View full image

The weapon symbolises what de Medici regards as the US government’s ‘moral hypocrisy’ on war crimes, a position that is emphasised by the tulips that adorn the rifle (illustrated). They are a symbol of male martyrdom in Iran and other parts of West Asia and continue the artist’s exploration of the flower as a masculine signifier. De Medici borrowed the image of the handshake that appears in the watercolour from the logo for the US Agency for International Development, while the two hands, one above the other (illustrated), represent money being exchanged in secretive deals, expanding on her interest in exposing ‘systems . . . that nobody seems to be able to escape from’.

De Medici adapted the vignette of two men locked in a sword fight with their severed heads kissing (illustrated) from a scene of bare-knuckled boxers in a book of nineteenth-century prints. The imagery expands on her scrutiny of male violence and the futility of armed combat.

eX de Medici, Australia b.1959 / System (This is the Place Where the Martyrs Grow) (detail) 2022 / Watercolour and tempera with gold leaf on paper / Three panels; two panels: 114 x 115cm; one panel: 114 x 145cm; 114 x 375cm (overall) / Collection: eX de Medici / © eX de Medici / View full image

Watch | eX de Medici discusses her work

Samantha Littley is Curator, Australian Art, QAGOMA.

‘eX de Medici: Beautiful Wickedness’ in 1.2 and 1.3 (Eric and Marion Taylor Gallery) was at GOMA from 24 June until 2 October 2023. ‘Beautiful Wickedness’ offered opportunities for dialogue with ‘Michael Zavros: The Favourite‘ presented in the adjacent gallery 1.1 (The Fairfax Gallery) and 1.2.