Henri Rivière: Thirty-six views of the Eiffel Tower

RIVIERE, Henri France 1864-1951 Lex trente xi Vuew de La Tour Eiffel (36 Views of the Eiffel Tower) 1888-1902 Bound edition of 36 colour lithographs, including 16 pages of text and 8 pages with titles and the imprint. In original slipcase. First edition, ed. of 500 22.7 x 26.9cm (sheet) new acquisition 712.2013 / View full image

The Gallery’s edition of 36 lithographs by printmaker, amateur photographer and shadow play theatre designer Henri Riviere (1864–1951), combine the influence of Japanese art in Europe in the late nineteenth century with the impact of the Eiffel Tower on the city of Paris.

Modelled on Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai’s (1760–1849) woodblock prints titled ‘Thirty‑six views of Mount Fuji’ c.1830–32 woodblock prints, Henri Riviere’s ‘Les Trente-six vues de la Tour Eiffel’ (‘Thirty-six views of the Eiffel Tower’) 1888–1902 is regarded as one of the finest examples of Japonisme, a term coined in France in the late nineteenth century to describe European artists’ stylistic borrowings from Japanese art and aesthetics.

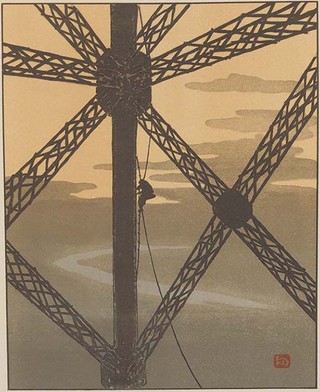

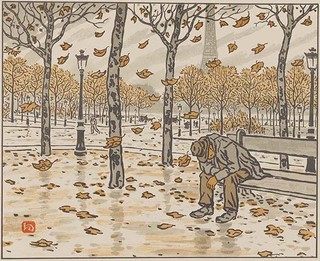

Following the introduction of ukiyo-e (‘pictures of the floating world’) woodblock prints to Paris in the 1860s, modern artists were drawn to their use of line, dramatic foreshortenings and unusual organisation of space, as well as to their subjects, which were often ordinary scenes from contemporary life. Far more than a pastiche of Hokusai, Riviere’s ‘views’ show the artist’s captivation, not only by the composition of ukiyo-e and the subdued palette of nineteenth-century manga (a term coined by Hokusai to describe his collections of sketches) but also by the monumentality of the Eiffel Tower’s wrought-iron architecture, which, visible from every quarter of the city, dominated the Paris skyline following its construction.

RIVIERE, Henri France 1864-1951 Lex trente xi Vuew de La Tour Eiffel (36 Views of the Eiffel Tower) 1888-1902 Bound edition of 36 colour lithographs, including 16 pages of text and 8 pages with titles and the imprint. In original slipcase. First edition, ed. of 500 22.7 x 26.9cm (sheet) new acquisition 712.2013 / View full image

In the prologue to the bound edition Les Trente-six vues de la Tour Eiffel, published in 1902, art critic Arsene Alexandre wrote of the Eiffel Tower:

When you suddenly appear to us through a skylight, or presiding over a council of chimneys, it is not you that coveys the turbulent life of a big city, but Paris itself, which you merely accentuate. When you enter the reverie of a vagabond in a garden or along a deserted street, or you find your way into the meditations of artists and flâneurs, you are like a giant walking stick with which our mind draws figures in the sand, distractedly, or plays with fallen leaves.1

While acknowledging its new-found prominence in the lives of all Parisians, Alexandre, like many of his contemporaries, was in no way enamoured by the shadow the controversial tower cast over the French capital — 300 metres high (986 feet), it was the tallest man-made structure in the world. Originally proposed to stand for only 20 years, Gustave Eiffel designed the tower as a symbol of French industrial prowess. It was widely criticised at the time for ‘overshadowing’ the capital’s historic landmarks. For Riviere, however, who had been given access to climb and photograph the tower prior to its completion, the structure represented a completely new type of spatial and visual beauty. When viewed from within, with Paris far below, massive iron girders backlit by the sky created abstract patterns, similar in effect to the shadow plays Riviere designed for the Chat Noir (Black Cat) cabaret. When viewed from the ground, the tower became an omnipresent backdrop to daily life in Paris and an icon of modernity.

Sally Foster is former Assistant Curator International Art (pre 1975), QAGOMA

1 Henri Riviere (trans. Alison Anderson), Thirty-Six Views of the Eiffel Tower by Henri Riviere, Prologue by Arsene Alexander, Chronicle Books and the Fine ArtsMuseum of San Francisco, 2010, p.95.

#HenriRiviere #QAGOMA