D Harding: Collecting Australia

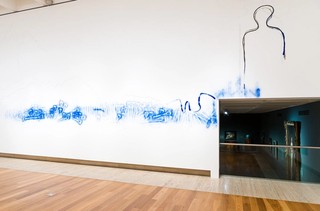

D Harding working on their commission Wall Composition in Reckitt’s Blue 2017 / Reckitt’s Blue laundry powder, charcoal and Grevillea robusta resin, incision into wall / Commissioned 2017 with funds from anonymous donors through the QAGOMA Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © D Harding / Photograph: C Callistemon © QAGOMA / View full image

In celebration of NAIDOC Week 2019, we invited award-winning author and Mununjali woman Ellen Van Neerven to develop a series of written responses entitled 'Collecting Australia’, which draw inspiration from works featured in our Australian Art Collection.

This is the first of three blogs combining our work with van Neerven’s poetry.

D Harding Wall Composition in Reckitt’s Blue 2017

D Harding, Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal peoples, Australia b.1982 / Wall Composition in Reckitt’s Blue (detail) 2017 / © D Harding / View full image

Collecting Australia

I wrote this series of poems, ‘Collecting Australia’ in two places: in the Gallery sitting before the works, and abroad in Germany, where I had a travel engagement.

I understand the newly developed Australian Collection as a reimagination. What is Australia anyway?

As a poet, I love the challenge of responding to artworks, meeting them with my own craft. I was deliciously drawn to D Harding’s Wall Composition in Reckitt’s Blue 2017 which covers a whole wall. I sat by this work for… I guess it was over an hour. The first poem I wrote was ‘Footnotes on a timeline’, and it captures all of my immediate feelings about the work. The shovel handle stencil motif in this artwork inspired ‘Call a spade a spade’. I saw an interview with D where they talked about the woman figure on the right in this artwork as representing women’s work and our matriarchal cultures so I wrote ‘The woman looking down’ about my own mother and grandmother and great-grandmother.

Watch | Harding introduces Wall composition in Reckitt’s Blue

Harding considers a fuller history of art production in Australia – from Indigenous (pre-European) to colonial to contemporary times. The tension in the Euro-centric perspective on Australia followed me in Germany, where I had a revelation of sorts. It is important to frame colonisation in two ways: events in Europe, events in Australia, there’s a direct relationship. I participated in a postcolonial walking tour in Bremen, in the north of Germany, where I saw what invading other countries had brought to Germany society. The city, the harbor and the waterways was created and shaped by this. Not ‘post’ anything, colonisation is still alive and well, it just goes by other names. By using a made-up spelling ‘Urup’ in my poem ‘Postcolonial musings in Urup’ I wanted to apply an Aboriginal sensibility to the word, and in doing so frame Europe as the other. Put the sharp microscope back on countries like Germany, The Netherlands, England and France, uncover the trails of exploitation, and see how they are still designed by default to exploit other countries.

While I hiked the Schwarzwald (Black Forest) in the south of Germany, I was struck by a feeling of sadness, haunting. I wrote about this in ‘a ship-shaped hole in the forest’, and I became interested to retrace the Cook’s Endeavour back to its source. Facing history from this angle, I felt oddly calm.

As well as having Mununjali Yugambeh (South East Queensland) heritage, I have Dutch heritage, and when I visited my family in the Netherlands I thought about my mixed-race body, two very different perspectives in my genes. ‘Funeral Plan’ is about this.

The following works reflect on what it means to ‘collect’ Australia, and how the tension between the Eu-Grip and Dhagan (Aboriginal land) manifests. I hope my words on this art in turn inspire future art and/ or creations/ imaginings.

Watch | D Harding creates Wall Composition in Reckitt’s Blue

Footnotes on a timeline

Burnt in blue to circumnavigate the strange land of evanescence, the blue line they call time moving all forward, bluing the blackfellas they dared called savage – you can’t steal from savages. There was infinite wealth to steal. Do you understand what it means to be a beneficiary of colonisation? Can we creep through the timeline and draw against the ancient-modern binary?

I can point on one side of the wave my ancestors’ story, I trace it through, they thought they cleaned it up but they built the shallowest grave. Their sold their soul for gold and coal and oil and we line our stomachs with water, it will be our armour, we are the people that can live inside our dreaming, live inside the sea, like inside a turtle’s heartbeat, live inside the sun on the sand, warm this country for centuries because we are the real entities. Don’t turn a blind eye please, all we need for you to see is that climate is our only bank. If we don’t have healthy water, air, earth, we got nothing. So where does your money go, where does your time go, my time and your time are on this timeline.

There’s time for us to read out all of the footnotes, go over the fine print. They burnt records of us in fires, the stole the evidence of our survival. But check my blood, I’m from here. This country is a haunted house, governments still playing cat chasing marsupial mouse. How many lies on your timeline? Have you ever felt like you’re just killing time? We’re still smoking sores. Let’s carbon date it, baby. We have time to read out all the footnotes of a timeline in Reckitt’s Blue.

D Harding working on their commission Wall Composition in Reckitt’s Blue

D Harding working on their commission Wall Composition in Reckitt’s Blue 2017 / Reckitt’s Blue laundry powder, charcoal and Grevillea robusta resin, incision into wall / Commissioned 2017 with funds from anonymous donors through the QAGOMA Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © D Harding / Photograph: C Callistemon © QAGOMA / View full image

Call a Spade a Spade

A heart a heart

A diamond a diamond

A club a club

Call it invasion not settlement

Call it genocide not colonisation

Call it theft not establishment

Don’t call January 26 Australia Day

Don’t shy away from telling the truth

Don’t say ‘no worries’ say ‘I worry’

for the future of our country, our environment

if we fail to listen and to act

Don’t say ‘we’re full’

Say we’re open

Call yourself an ally

Call yourself a mate

D Harding working on their commission Wall Composition in Reckitt’s Blue

D Harding working on their commission Wall Composition in Reckitt’s Blue 2017 / Reckitt’s Blue laundry powder, charcoal and Grevillea robusta resin, incision into wall / Commissioned 2017 with funds from anonymous donors through the QAGOMA Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © D Harding / Photograph: C Callistemon © QAGOMA / View full image

The woman looking down

is my mother

she’s stressing the way

come here my jahjam

the ancestors whisper

come now, sit on my shoulder

you’re safe

you listen

you think of us

“Postcolonial” musings in Urup

Urup colonised itself

and now has a belly ache

like the snake that ate

a kangaroo

local languages

hang in the balance

the river pushed

for commerce

coffee grounds on the

railway tracks

cotton seeds

in the air

merchant houses

built on backs

wolves asked

welcomed back

beavers needed

to clean the river

the red squirrel

fends of the grey

migrant children play football

on the hills

gold draped buildings

fester in the city

here their traditions honoured

so why isn’t ours?

let’s get the U-Grip

of our Dhagun

A ship-shaped hole in the forest

Such a sad sight: a ship-shaped hole in the forest

still recovering from the fright of colonisation

The straightest pine cut into masts

elm into keel and stern post

white oak into hull, floors and futtocks

For the farms: streams of straw and cattle

graze on the deforested floor.

While the ship sails in the southern seas

the ship-shaped hole

thousands of years deep

aches and aches

the people burn their furniture to stay warm

try to regenerate with new trees

left with commercial forests

and waldsterben.

no consent was asked from the materials of “discovery”

in Yugambeh our names for boat and

tree that makes the boat are the same

material handled with care

spirit lives

in the same name

so do I call you tree or mast

as I walk through the wood

full of so many ship-shaped holes?

Funeral Plan

what can you do with your body?

it’s just one body

my Aunt and Uncle are burying themselves in a curated forest

it costs $4000

when history becomes necessary

the sadness belongs to me

I am not aware of my power

you watch me build my weapon

Ellen van Neerven (Meanjin, July 2019)

D Harding

Working in diverse techniques and traditions, including painting, installation, sculpture, domestic handicrafts, stenciling, woodcarving and silicone casting, D Harding is renowned for works that explore the untold histories of their communities. Harding has a particular interest in ideas of cultural continuum and investigates the social and political realities experienced by their family under government control in Queensland, with a focus on matrilineal antecedents.

D Harding, Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal peoples, Australia b.1982 / Wall Composition in Reckitt’s Blue (detail) 2017 / Reckitt’s Blue laundry powder, charcoal and Grevillea robusta resin, incision into wall / Commissioned 2017 with funds from anonymous donors through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © D Harding / View full image

This project is part of ‘Drawing from the Collection’, a series of programs which invite you to take inspiration and draw ideas from the QAGOMA Collection through ongoing experiences from special events, to daily drop-in drawing.

Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA)

Brisbane, Australia