Between earth and sky: Indigenous contemporary art from Taiwan

Yuma Taru, Atayal people, Taiwan b.1963 / The spiral of life – the tongue of the cloth (yan pala na hmali) – a mutual dialogue (installation view) 2021 / Ramie suspended from metal threads / 500 x 250cm / Commissioned for APT10 / © & courtesy: Yuma Taru / View full image

A presentation of new work by eight artists from Taiwan’s Atayal, Paiwan and Truku communities, in ‘The 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT10) project Between Earth and Sky offers a glimpse of the vitality and diversity of indigenous contemporary practice in Taiwan.

Installation view of ‘The 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT10) project Between Earth and Sky / Photograph: Natasha Harth © QAGOMA / View full image

Installation view of ‘The 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT10) project Between Earth and Sky / Photograph: Natasha Harth © QAGOMA / View full image

As four decades of martial law in Taiwan were relaxed at the end of the 1980s, the voices of the burgeoning democracy movement were joined by those of the island’s indigenous peoples, seeking official recognition, self-determination and the right to use personal names in their own language. With linguistic and anthropological links across the Austronesian world, Taiwan’s indigenous people have made the island their home for more than 5000 years. Since the early seventeenth century, successive waves of colonisation by European and Asian powers have seen them subjugated, dispossessed and assimilated, with loss of culture and language accompanying lack of access to land, education and economic opportunities. The emergence of contemporary art by indigenous artists provided an avenue for cultural revitalisation, the expression of identity and the creative consideration of current realities. On the other hand, it also enabled artists of indigenous heritage to participate in the wider field of contemporary art, rather than being framed as practitioners of ‘folk art’ or ‘craft’, or indeed being restricted to representing their ethnicity.

Anli Genu, Atayal people, Taiwan b.1958 / Weave my face 2021 / Oil and mixed media on canvas / 175 x 368cm / © Anli Genu / Image courtesy: The artist and Taiwan Indigenous Peoples Cultural Development Centre / View full image

Aluaiy Pulidan, Paiwan people, Taiwan b.1970 / Find a habitat (installation view, detail) 2021 / Wool, ramie, cotton, copper, silk / © Aluaiy Pulidan / Courtesy: The artist and Taiwan Indigenous Peoples Cultural Development Centre / Photograph: Natasha Harth © QAGOMA / View full image

While Paiwan artist Er Ge and Beinan artist Haku were included in the 1996 Taipei Biennale, the terms ‘contemporary’ and ‘aboriginal’ were not used together in art discourse until 1999.[1] The establishment of the first dedicated collecting program by a public institution came as recently as 2006, with the launch of Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts’ ‘Austronesian Contemporary Art Development Plan’. Yet, while institutional frameworks are relatively new, indigenous artists have been producing incisive, innovative work for at least 30 years, when the likes of Amis carver and performance artist Rahic Talif and Paiwan sculptor Sakuliu Pavavalung began forging international networks and mentoring younger artists. The field is wide and diverse, reflecting the distinctiveness of Taiwan’s indigenous peoples, with 16 official ethnic identities and many more in the process of seeking recognition.

Yuma Taru, Atayal people, Taiwan b.1963 / The spiral of life – the tongue of the cloth (yan pala na hmali) – a mutual dialogue (installation view) 2021 / Ramie suspended from metal threads / 500 x 250cm / Commissioned for APT10 / © & courtesy: Yuma Taru / View full image

Masiswagger Zingrur, Paiwan people, Taiwan b.1972 / Dialogue – token 2021 (detail) / Kilned clinker soil, gravel / 18 parts / © Masiswagger Zingrur / Courtesy: The artist and Taiwan Indigenous Peoples Cultural Development Centre / View full image

Ruby Swana, Amis people, Taiwan b.1959 / Dancer of light 2021 (detail) / Aluminium foil, cellophane, hot glue, epoxy resin, clay/ Commissioned for APT10 / © Ruby Swana / Image courtesy: The artist and Taiwan Indigenous Peoples Cultural Development Centre / Photograph: Natasha Harth © QAGOMA / View full image

Between Earth and Sky provides a hint of this vast and vibrant field, focusing on practices that draw on indigenous histories and cosmologies to propose more sustainable futures. Paintings by exhibition co-curator Pavavalung (illustrated) and Atayal pastor Anli Genu (illustrated), as well as elaborate soft sculptures by Paiwan leader Aluaiy Pulidan (illustrated), use art as an expression of collective identity, reworking customary motifs into new and innovative forms. For Atayal weaver Yuma Taru (illustrated) and Paiwan ceramicist Masiswagger Zingrur (illustrated), art is a means of reviving endangered traditions and techniques; both artists filter their decades-long research into dazzling installations. Sculptor Ruby Swana (illustrated) and choreographer Fangas Nayaw of the Amis people of Taiwan’s Pacific coast (illustrated) approach the threat of climate change from the perspective of tribal knowledge, respectively exploring zero-waste living and an ‘indigenous punk’ futurism that resonates with the cross-gender, cross-medium performances of Truku artist Dondon Hounwn (illustrated).

Fangas Nayaw, Amis people, Taiwan b.1987 / La XXX punk 2021 / Four-channel video: 16:9, 30 minutes, colour, sound / © Fangas Nayaw / Image courtesy: The artist and Taiwan Indigenous Peoples Cultural Development Centre / Photograph: Natasha Harth © QAGOMA / View full image

Dondon Hounwn, Truku people, Taiwan b.1985 / 3M – MSPING Adornment (from ‘3M – Three Happenings’ series) (still) 2018 / Single-channel video: 16:9, colour,

sound / © Dondon Hounwn / Courtesy: The artist and Taiwan Indigenous Peoples Cultural Development Centre / View full image

The presentation of Between Earth and Sky in APT10 follows the inclusion of striking paintings by Truku/Atayal artist Idas Losin in APT9. It offers a further glimpse of the vitality and diversity of this exciting, expansive field of contemporary practice, deepening the APT’s engagement with First Nations artists throughout the region while enhancing the potential for dialogue with artists and communities across the Asia Pacific.

Reuben Keehan is Curator, Contemporary Asian Art, QAGOMA

This is an expanded version of an article originally published in the QAGOMA Members’ magazine, Artlines, no.4, 2021

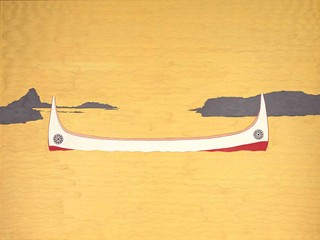

Idas Losin, Taiwan b.1976 / Floating 2017 / Oil on canvas / 135 x 179cm / Purchased 2019. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Idas Losin / View full image

Endnotes

- ^ Sophie McIntyre, ‘The public rise and exhibition of Taiwan Indigenous art and its role in nation-building and reconciliation’ in Huang Chia-yuan, Daniel Davies and Dafydd Fell (eds), Taiwan’s Contemporary Indigenous Peoples, Routledge, Oxon and New York, 2021, pp.105–27.