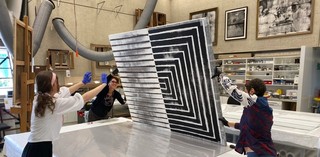

The QAGOMA Research Library is located at GOMA / View full image

Library

QAGOMA's Research Library holds an extensive number of QAGOMA Conservation Research Papers.

Open: 10.00am – 4.45pm, Tue–Fri

Gallery of Modern Art, Level 3

Closed weekends, Mondays and public holidays.