Looking Out, Looking In Exploring the Self-Portrait

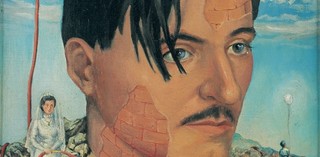

James Gleeson, Australia 1915–2008 / Structural emblems of a friend (self portrait) 1941 / Oil on canvas board / 46 x 35.6cm / Purchased 1984 with the assistance of the John Darnell Bequest / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © QAGOMA / View full image

When

8 Mar 2025 – 15 Aug 2027

Admission

Free

About

Contemporary society has become increasingly attuned to the self-image through social media’s 'selfie' culture and reality TV, providing a fascinating backdrop in which to examine the self-portrait today.

'Looking Out, Looking In' explores the genre of the self-portrait, a distinct form of portraiture in which subject and artist are one. The exhibition examines the human tendency to envisage oneself. While some of the artists look inwards and reflect on themselves in self-effacing ways, or may just be intrigued by their own image, others seek to project an image or identity in more flamboyant displays.

Tour Resources

Nora Heysen, Australia 1911–2003 / Self portrait 1938 / Oil on canvas laid on board / 39.5 x 29.5cm / Purchased 2011 with funds from Philip Bacon AM through the QAG Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Lou Klepac / View full image

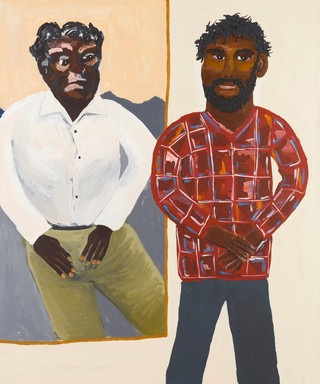

Vincent Namatjira, Western Aranda people, Australia b.1983 / Albert and Vincent 2014 / Synthetic polymer paint on linen / 120 x 100cm / Gift of Dirk and Karen Zadra through the QAGOMA Foundation 2014. Donated through the Australian Government's Cultural Gifts Program / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Vincent Namatjira/Copyright Agency / View full image

James Gleeson, Australia 1915–2008 / Structural emblems of a friend (self portrait) 1941 / Oil on canvas board / 46 x 35.6cm / Purchased 1984 with the assistance of the John Darnell Bequest / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © QAGOMA / View full image

Laith Mcgregor, Australia b.1977 / Maturing (still) 2008 / Single-channel video (DVD): 30 minutes, colour, silent / Purchased 2011. John Darnell Bequest / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Laith McGregor / View full image

Marjorie Fletcher, Australia 1912–88 / Self-torso 1934, cast 1992 / Bronze / 52.5 x 22 x 19.8cm (irreg.) / Gift of Don and Alison Mitchell through the QAG Foundation 2005. Donated through the Australian Government's Cultural Gifts Program / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Marjorie Fletcher/Copyright Agency / View full image