Education Resources

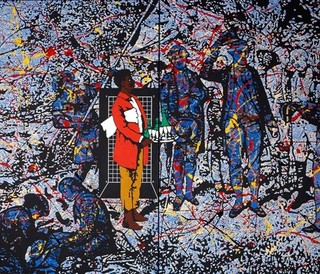

Students participating in a workshop / Photograph: J Ruckli © QAGOMA / View full image

Connect curriculum with exhibitions and our Collection through a range of learning resources for primary and secondary levels.

Featured Resources

-

Creative Generation: In Residence 2024 Digital Exhibition

-

Olafur Eliasson Presence

- When 6 Dec 2025 – 12 Jul 2026

- Where GOMA

-

Archie Moore: kith and kin

- When 27 Sep 2025 – 18 Oct 2026

- Where GOMA

-

Wonderstruck

- When 28 Jun – 6 Oct 2025

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation 2025: Excellence Awards in Visual Art

- When 31 May – 31 Aug 2025

- Where GOMA

First Nations Artists

See all First Nations Artists resources-

Archie Moore: kith and kin

- When 27 Sep 2025 – 18 Oct 2026

- Where GOMA

-

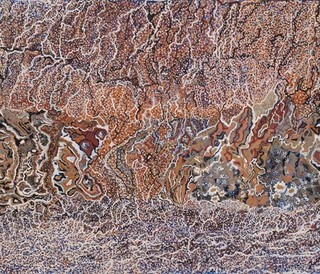

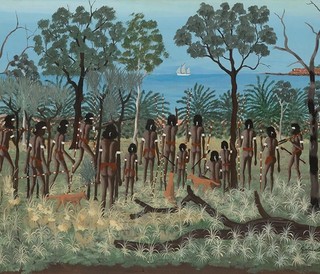

Mavis Ngallametta: Show me the way to go home

- When 21 Mar 2020 – 7 Feb 2021

- Where QAG

-

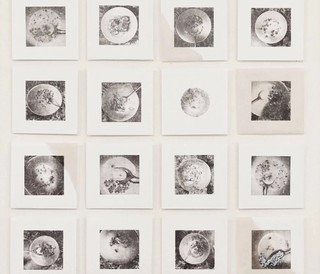

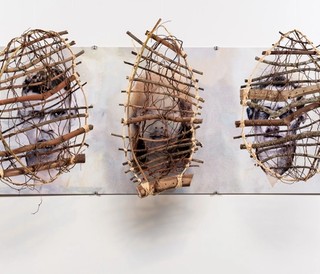

Shirley Macnamara: Dyinala, Nganinya

- When 21 Sep 2019 – 1 Mar 2020

- Where QAG

-

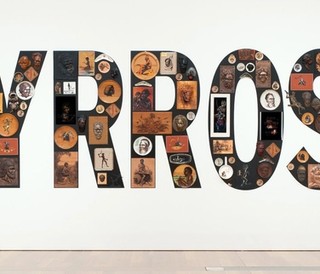

Tony Albert: Visible Resources

- When 2 Jun – 7 Oct 2018

- Where QAG

Australian Artists

See all Australian Artists resources-

eX de Medici: Beautiful Wickedness Resource

- When 24 Jun – 2 Oct 2023

- Where GOMA

-

Michael Zavros: The Favourite Resource

- When 24 Jun – 2 Oct 2023

- Where GOMA

-

Quilty Resources

- When 29 Jun – 13 Oct 2019

- Where GOMA

-

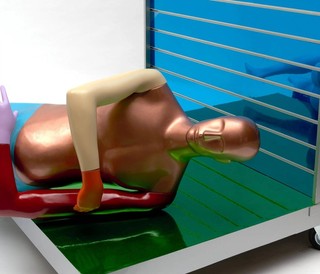

Patricia Piccinini: Curious Affection Resources

- When 24 Mar – 5 Aug 2018

- Where GOMA

Asian & Pasifika Artists

See all Asian & Pasifika Artists resources-

Yayoi Kusama: Life is the Heart of a Rainbow Resource

- When 4 Nov 2017 – 11 Feb 2018

- Where GOMA

-

Michael Parekowhai: The Promised Land

- When 28 Mar – 21 Jun 2015

- Where GOMA

-

Cai Guo-Qiang: Falling Back to Earth

- When 23 Nov 2013 – 12 May 2014

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation: In Residence 2023 Digital Exhibition

International Artists

See all International Artists resources-

Olafur Eliasson Presence

- When 6 Dec 2025 – 12 Jul 2026

- Where GOMA

-

European Masterpieces from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Resources

- When 12 Jun – 17 Oct 2021

- Where GOMA

-

Gerhard Richter: The Life of Images

- When 14 Oct 2017 – 4 Feb 2018

- Where GOMA

-

Cindy Sherman

- When 28 May – 3 Oct 2016

- Where QAG & GOMA

Exhibition Resources

See all Exhibition resources-

Archie Moore: kith and kin

- When 27 Sep 2025 – 18 Oct 2026

- Where GOMA

-

Olafur Eliasson Presence

- When 6 Dec 2025 – 12 Jul 2026

- Where GOMA

-

Wonderstruck

- When 28 Jun – 6 Oct 2025

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation 2025: Excellence Awards in Visual Art

- When 31 May – 31 Aug 2025

- Where GOMA

Asia Pacific Triennial

See all Asia Pacific Triennial resources-

The 11th Asia Pacific Triennial Resources

- When 30 Nov 2024 – 27 Apr 2025

- Where QAG & GOMA

-

APT10 Resource

- When 4 Dec 2021 – 25 Apr 2022

- Where QAG & GOMA

-

APT9 Resources

- When 24 Nov 2018 – 28 Apr 2019

- Where QAG & GOMA

-

APT8 Resources

- When 21 Nov 2015 – 10 Apr 2016

- Where QAG & GOMA

Creative Generation

See all Creative Generation resources-

Creative Generation: In Residence 2024 Digital Exhibition

-

Creative Generation 2025: Excellence Awards in Visual Art

- When 31 May – 31 Aug 2025

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation 2023 Excellence Awards in Visual Art

- When 22 Apr – 6 Aug 2023

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation: In Residence 2023 Digital Exhibition

All Resources

-

21st Century: Art in the First Decade

- When 18 Dec 2010 – 26 Apr 2011

- Where GOMA

-

Air Resources

- When 26 Nov 2022 – 23 Apr 2023

- Where GOMA

-

Andy Warhol

- When 8 Dec 2007 – 13 Apr 2008

- Where GOMA

-

APT5 Resources

- When 2 Dec 2006 – 27 May 2007

- Where QAG & GOMA

-

APT6 Resources

- When 5 Dec 2009 – 5 Apr 2010

- Where QAG & GOMA

-

APT7 Resources

- When 8 Dec 2012 – 14 Apr 2013

- Where QAG & GOMA

-

APT8 Resources

- When 21 Nov 2015 – 10 Apr 2016

- Where QAG & GOMA

-

APT9 Resources

- When 24 Nov 2018 – 28 Apr 2019

- Where QAG & GOMA

-

APT10 Resource

- When 4 Dec 2021 – 25 Apr 2022

- Where QAG & GOMA

-

Archie Moore: kith and kin

- When 27 Sep 2025 – 18 Oct 2026

- Where GOMA

-

Art Academy Digital Exhibition

-

Cai Guo-Qiang: Falling Back to Earth

- When 23 Nov 2013 – 12 May 2014

- Where GOMA

-

Cindy Sherman

- When 28 May – 3 Oct 2016

- Where QAG & GOMA

-

Contemporary Australia Optimism

- When 15 Nov 2008 – 22 Feb 2009

- Where GOMA

-

Contemporary Australia: Women

- When 21 Apr – 22 Jul 2012

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation 2009 Artists' Statements

- When 13 Mar – 17 May 2009

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation 2011 Artists' Statements

- When 28 May – 21 Aug 2011

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation 2012 Artists' Statements

- When 3 Mar – 3 Jun 2012

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation 2013 Artists' Statements

- When 10 May – 11 Aug 2013

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation 2014 Artists' Statements

- When 5 Apr – 22 Jun 2014

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation 2015 Artists' Statements

- When 18 Apr – 12 Jul 2015

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation 2016 Artists' Statements

- When 7 May – 14 Aug 2016

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation 2017 Artists' Statements

- When 8 Apr – 30 Jul 2017

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation 2018 Artists' Statements

- When 21 Apr – 29 Jul 2018

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation 2019 Artists' Statements

- When 25 May – 25 Aug 2019

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation 2020

- When 18 Apr – 22 Jun 2020

-

Creative Generation 2021 Excellence Awards in Visual Art

- When 24 Apr – 8 Aug 2021

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation 2022 Excellence Awards in Visual Art

- When 28 May – 21 Aug 2022

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation 2023 Excellence Awards in Visual Art

- When 22 Apr – 6 Aug 2023

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation 2024: Excellence Awards in Visual Art

- When 27 Apr – 25 Aug 2024

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation 2025: Excellence Awards in Visual Art

- When 31 May – 31 Aug 2025

- Where GOMA

-

Creative Generation: In Residence 2023 Digital Exhibition

-

Creative Generation: In Residence 2024 Digital Exhibition

-

David Lynch: Between Two Worlds

- When 14 Mar – 8 Jun 2015

- Where GOMA

-

Embodied Knowledge Resources

- When 13 Aug 2022 – 22 Jan 2023

- Where QAG

-

Eugene von Guérard: Nature Revealed

- When 17 Dec 2011 – 4 Mar 2012

- Where QAG

-

European Masterpieces from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Resources

- When 12 Jun – 17 Oct 2021

- Where GOMA

-

eX de Medici: Beautiful Wickedness Resource

- When 24 Jun – 2 Oct 2023

- Where GOMA

-

Fairy Tales Resources

- When 2 Dec 2023 – 28 Apr 2024

- Where GOMA

-

Gerhard Richter: The Life of Images

- When 14 Oct 2017 – 4 Feb 2018

- Where GOMA

-

Get Up, Stand Up: Indigenous Australian Art Collection

- When 19 Dec 2020 – 15 Jan 2023

- Where QAG

-

Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Man, The Image & The World

- When 27 Aug – 27 Nov 2011

- Where GOMA

-

Iris van Herpen Resources

- When 29 Jun – 7 Oct 2024

- Where GOMA

-

Jon Molvig: Maverick

- When 14 Sep 2019 – 2 Feb 2020

- Where QAG

-

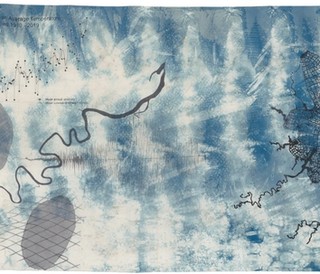

Judy Watson

- When 23 Mar – 11 Aug 2024

- Where QAG

-

Land, Sea and Sky: Contemporary Art of the Torres Strait Islands

- When 1 Jul – 9 Oct 2011

- Where GOMA

-

Learning Collection

-

Margaret Olley: A Generous Life Resources

- When 15 Jun – 13 Oct 2019

- Where GOMA

-

Marvel: Creating the Cinematic Universe

- When 27 May – 3 Sep 2017

- Where GOMA

-

Matisse: Drawing Life

- When 3 Dec 2011 – 4 Mar 2012

- Where GOMA

-

Mavis Ngallametta: Show me the way to go home

- When 21 Mar 2020 – 7 Feb 2021

- Where QAG

-

Mayfair: (Swamp Rats) Ninety-Seven Signs for C.P., J.P., B.W., G.W. & R.W. 1994-94

- When 27 Jun – 5 Oct 2015

- Where GOMA

-

Michael Parekowhai: The Promised Land

- When 28 Mar – 21 Jun 2015

- Where GOMA

-

Michael Zavros: The Favourite Resource

- When 24 Jun – 2 Oct 2023

- Where GOMA

-

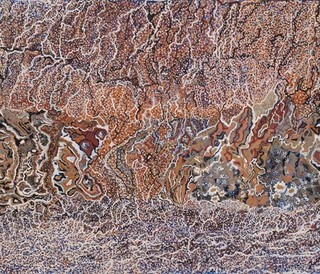

Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori: Dulka Warngiid – Land of all

- When 21 May – 28 Aug 2016

- Where QAG

-

Modern Woman: Daughters and Lovers 1850 — 1918 Drawings from the Musée d’Orsay, Paris

- When 24 Mar – 24 Jun 2012

- Where QAG

-

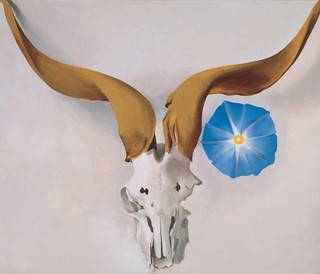

O'Keeffe, Preston, Cossington Smith: Making Modernism

- When 11 Mar – 11 Jun 2017

- Where QAG

-

Olafur Eliasson Presence

- When 6 Dec 2025 – 12 Jul 2026

- Where GOMA

-

Patricia Piccinini: Curious Affection Resources

- When 24 Mar – 5 Aug 2018

- Where GOMA

-

Picasso & His Collection

- When 9 Jun – 14 Sep 2008

- Where GOMA

-

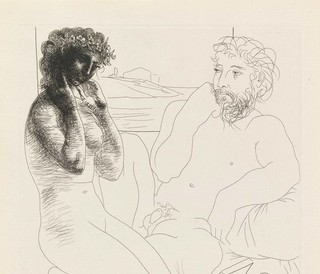

Picasso: The Vollard Suite Resource

- When 2 Dec 2017 – 15 Apr 2018

- Where QAG

-

Portrait of Spain: Masterpieces from the Prado

- When 21 Jul – 4 Nov 2012

- Where QAG

-

Quilty Resources

- When 29 Jun – 13 Oct 2019

- Where GOMA

-

Ron Mueck

- When 8 May – 1 Aug 2010

- Where GOMA

-

Roy and Matilda: Australian Art Collection

-

Sculpture is Everything

- When 18 Aug – 28 Oct 2012

- Where GOMA

-

Shirley Macnamara: Dyinala, Nganinya

- When 21 Sep 2019 – 1 Mar 2020

- Where QAG

-

Sublime: Contemporary works from the Collection

- When 30 Aug 2014 – 24 May 2015

- Where QAG

-

Sugar Spin (GOMA Turns 10)

- When 3 Dec 2016 – 17 Apr 2017

- Where GOMA

-

Surrealism: The Poetry of Dreams

- When 11 Jun – 2 Oct 2011

- Where GOMA

-

The 11th Asia Pacific Triennial Resources

- When 30 Nov 2024 – 27 Apr 2025

- Where QAG & GOMA

-

The China Project

- When 28 Mar – 28 Jun 2009

- Where GOMA

-

The Motorcycle: Design, Art, Desire Resources

- When 28 Nov 2020 – 26 Apr 2021

- Where GOMA

-

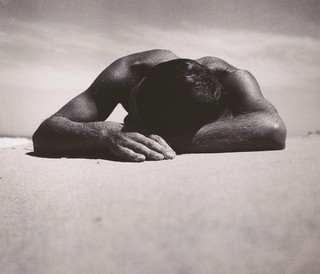

The Photograph and Australia

- When 4 Jul – 11 Oct 2015

- Where QAG

-

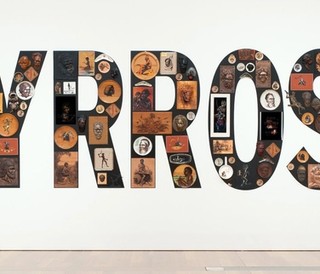

Tony Albert: Visible Resources

- When 2 Jun – 7 Oct 2018

- Where QAG

-

Transitions Now: Contemporary Aboriginal Forms and Images from the Collection

- When 6 Aug 2022 – 25 Jun 2023

- Where GOMA

-

Unfinished Business: The Art of Gordon Bennett Resources

- When 7 Nov 2020 – 21 Mar 2021

- Where GOMA

-

Unnerved: The New Zealand Project

- When 1 May – 4 Jul 2010

- Where GOMA

-

Valentino, Retrospective Past/Present/Future

- When 7 Aug – 14 Nov 2010

- Where GOMA

-

Water

- When 7 Dec 2019 – 23 Mar 2020

- Where GOMA

-

We Can Make Another Future: Japanese Art After 1989

- When 6 Sep 2014 – 20 Sep 2015

- Where GOMA

-

William Robinson

- When 9 May – 7 Oct 2013

- Where QAG

-

Wonderstruck

- When 28 Jun – 6 Oct 2025

- Where GOMA

-

Yayoi Kusama: Life is the Heart of a Rainbow Resource

- When 4 Nov 2017 – 11 Feb 2018

- Where GOMA

-

Yayoi Kusama: Look Now See Forever

- When 18 Nov 2011 – 11 Mar 2012

- Where GOMA